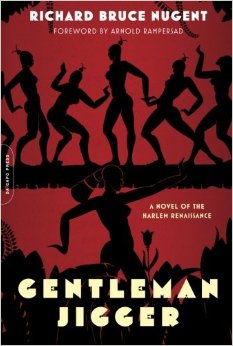

Richard Bruce Nugent’s Gentleman Jigger (Da Capo Press, 2008) remains a curious product from the greater Harlem or “New Negro” Renaissance era (ca. 1919–1940). It is also one of the period’s few significant lost novels and best satires, one that only saw publication in 2008 thanks to Nugent’s friend and editor, Thomas Wirth. Composed from the late 1920s and early 1930s, Gentleman Jigger shares a curious history with Wallace Thurman’s satirical novel, Infants of the Spring (1932), including its basic plot, several crucial scenes, and decidedly similar characters. Each novel is a roman à clef; only the thinnest veils disguise primary and secondary characters from the historical figures being lampooned. Each offers revealing insights regarding the younger writers affiliated with the New Negro movement in New York—dubbed the “Niggerati” by members Thurman and author Zora Neale Hurston—particularly their ambitions, squabbles, and quirks. Both novels focus upon the struggles among the movement’s artists and writers to develop a useful or consistent aesthetic, one that would encourage better or more sustained creative work that owed less to desires to please black or white audiences and more to a will to modernity.

Perhaps equally important, both novels unintentionally reveal their vexed authorship. Though Thurman obviously published Infants of the Spring during the movement, albeit after its late 1920s peak, Nugent never completed a final draft. Wirth notes in his introduction to Gentleman Jigger that he found several partial manuscripts in Nugent’s papers after his death and assembled the published text from the latest versions of the novel’s various sections and chapters. Despite this status, the novel generally coheres, at least to the extent that its quasi-autobiographical protagonist, Stuartt Brennan, anchors the plot.

As even the most casual reader will notice, though, Gentleman Jigger comprises two books. The first follows a basic plot nearly identical to Infants of the Spring, depicting many of the same events during the most crucial period for the young Harlem Literati circa 1925–27. These include the first encounters among Thurman, Nugent, Langston Hughes, Rudolph Fisher, Eric Walrond, Aaron Douglas, Zora Neale Hurston, Louise Thompson, Helene Johnson, Jessie Redmon Fauset, Nella Larsen, Carl Van Vechten, Alain Locke, and W. E. B. Du Bois as they sought to invent, cement, and define the New Negro Renaissance as a foundation for black artistic expression for the twentieth century. The protagonist, Stuartt Brennan, combines elements of Nugent and Thurman’s personalities and personal histories.

Detailing Stuartt’s evolving queer sexuality and exploits as a lover and companion both to Italian gangsters and an actress/singer, the second half departs almost entirely from the first, with the Harlem group virtually absent. If Gentleman Jigger had been published in the early 1930s in its current form, this portion would have been both innovative and controversial. In nearly every respect an example of erotica—albeit not an explicit one—it extends Nugent’s innovations from his earlier story “Smoke, Lilies, and Jade,” which was published in the lone issue of Fire!! magazine—the “Niggerati’s” debut—in November 1926, and edited by Thurman. “Smoke, Lilies, and Jade” simultaneously analyzes sexuality, race, gender, and ethnicity in overlapping relationships drawn directly from the Harlem writers’ interactions and Nugent’s experiences. It also stands as the first work by an African American to feature an openly bisexual character. Had Gentleman Jigger beaten Infants of the Spring into print, it would have been the first novel to do the same.

Though Gentleman Jigger certainly merits analysis under a queer studies or lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgender aegis, its second half bears only the most tentative relationship to its first. This may be attributable to Nugent losing interest in completing and publishing his work. Thurman and Nugent roomed together for a time, and, in Nugent’s words, complemented each other artistically. Thurman would help Nugent with his writing, while Nugent would critique and edit his roommate and friend’s work. The line dividing Thurman’s authorship of Infants of the Spring from Nugent’s composition of Gentleman Jigger remains entirely fluid to this day; as Thomas Wirth notes in his introduction to Gentleman Jigger, “Nugent and Thurman were working on their novels at the same time; Thurman finished his first. Its appearance in 1932 effectively blocked whatever prospects for publication Gentleman Jigger may have had.... The fact that Thurman’s novel was published first does not necessarily mean that Nugent imitated Thurman. Indeed…Nugent alleged the opposite: that Thurman copied from him” to create a superficially similar roman à clef, but one with a different tenor and emphasis.[i] For his part, Nugent allowed that he bore no ill-will towards Thurman and any unacknowledged use of his work; according to David Levering Lewis’s notes from his 1974 interview with Nugent, both “were borrowing from one another and knew it…[Nugent] in fact suggests that [Thurman] appropriated much of his novel—but it was ok.”[ii]

That Nugent and Thurman borrowed liberally from each other makes the exact provenance for each novel difficult to determine. It certainly seems reasonable that after Thurman published his novel, it obviated any of Nugent’s attempts to publish his own. Moreover, Nugent professed and lived a strongly Bohemian credo, which meant that he generally produced his art on his own schedule and made few concerted efforts to publish or display his work. Regardless of the point when Nugent returned to his work, the second half indicates that Nugent as author no longer seems interested in understanding the New Negro movement’s primary flaw: its members’ lopsided ratio of loquaciousness over action and artistic integrity undermined their own efforts.

This same dilemma applies, perhaps, to Nugent himself. The fluid authorial boundaries that inspired Thurman’s work appears to have deprived the public of Nugent’s own for far too long. Now that it is available, though, we have an opportunity and obligation to place one of the twentieth century’s most intriguing novels back at the center of the New Negro movement.

Darryl Dickson-Carr is an associate professor of English at Southern Methodist University, where he teaches courses in twentieth-century American literature, African American literature, and satire. His research focuses primarily upon the “New Negro” or Harlem Renaissance and African American satirical works in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. He is the author of Spoofing the Modern: The Role of Satire in the Harlem Renaissance (forthcoming; University of South Carolina Press, 2015), The Columbia Guide to Contemporary African American Fiction (Columbia University Press, 2005), which won an American Book Award in 2006, and African American Satire: The Sacredly Profane Novel (University of Missouri Press, 2001).

[i] Thomas Wirth, “Introduction,” Gentleman Jigger, p. xiii.

[ii] David Levering Lewis, Interview with Bruce Nugent, September 11, 1974. “Voices from the Renaissance,” David Levering Lewis Collection, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.

Add new comment