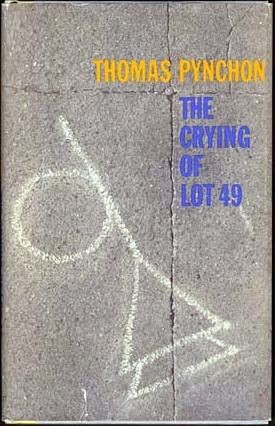

This December marks the fiftieth anniversary of Oedipa Maas’s first appearance in print, as part of “The World (This One), the Flesh (Mrs. Oedipa Maas), and the Testament of Pierce Inverarity,” a story Thomas Pynchon published in the December 1965 issue of Esquire. Oedipa’s novel, The Crying of Lot 49, would be published in full in March 1966. Where would postmodern literature be without her? Where would critical definitions of postmodernism be? And why does this slim novel continue to exert such power over us? As a ubiquitous book turns a half-century old, these are questions worth reflecting on anew.

From Borges to Gaddis and Barth, there are other sources besides Lot 49 for the figure of the metaphysical detective, other heady ruminations on entropy and conspiracy, other renderings of failed communication and hegemonic control. But it is difficult to imagine distilling an explanation of literary postmodernism—whether in synopses of the field or in an undergraduate syllabus moving quickly along—without a discussion of those crystalline final lines from Pynchon’s book: “Passerine spread his arms in a gesture that seemed to belong to the priesthood of some remote culture; perhaps to a descending angel. The auctioneer cleared his throat. Oedipa settled back, to await the crying of lot 49.” That readers reach this tense deferral of revelation after 183 pages and not 776 (Gravity’s Rainbow [1973]), 750 (Giles Goat-Boy [1966]), or 1079 (Infinite Jest [1996]) is key to the staying power of Pynchon’s novelette. In a period populated by memorable mega-books, Lot 49 has the advantage of not blowing a syllabus (or a conference paper, or an encyclopedia entry) out of the water.

A North American English major, or a non-humanities student fulfilling a survey requirement, is almost bound to encounter Lot 49 on one of those syllabi, a ready example of postwar US fiction, black humor, Cold War culture, or the contingencies of interpreting literary art at all. Somewhere the writer who in 2030 will be crowned the heir to David Foster Wallace (who couldn’t have written The Broom of the System [1987] without the model of Lot 49) is reading Pynchon’s book for a college class, right before moving on to White Noise (1985). In figures no doubt fueled by campus bookstores, Lot 49 still sells (according to J. Kerry Grant, author of a guide to the novel’s allusions) between fifteen and twenty thousand copies a year. The MLA database counts, from the early 1970s to 2015, 330 articles, books, and dissertations that list Lot 49 among their subjects (for comparison, Lolita’s number, since 1958, is 185). Those stats may seem to represent critical saturation, but Lot 49, having accommodated readings from the deconstructive to the Deleuzean, may well be able to maintain a perennial resilience as it makes the turn into its sixth decade. It is the first of what a recent collection edited by Scott McClintock and John Miller calls Pynchon’s “California novels,” a new way of distinguishing the slighter novels—Lot 49, Vineland (1990), and Inherent Vice (2008)—from the bigger books. Historicized readings (such as Joanna Freer’s linking of Oedipa to the 1960s and the women’s movement) are still relatively rare and due to grow. While Doc Sportello in Inherent Vice launched a few more dissertation chapters by revitalizing Pynchon’s intersections with detective fiction, Maxine Tarnow, the tough forensic accountant investigating 9/11 in Bleeding Edge (2013), gives critics still more reasons to connect the twenty-first century back to 1966: Maxine in some ways revises Oedipa’s quest to find “Silent Tristero’s Empire” for an age of globalization, terrorism, neoliberalism, and the postal networks known as the Internet and the “Deep Web.”

But it’s not only the teachers and critics who have kept Lot 49 alive (indeed, I’m sure there are some who will say they’ve killed it). When NBC’s hit comedy Parks and Recreation set its 2009 pilot episode around a “Lot 48,” a pit that might be turned into a public park, the joke nodded to Pynchon’s pop-cultural ownership of 49, second only in the literary world perhaps to Joseph Heller’s lock on 22. Pynchon himself, with his wacky touch, injected the book into the simulacral TV world it once anatomized when, in a 2004 episode of The Simpsons (in jokes he apparently wrote for himself), he judged Marge’s chicken wings “V-licious!” and said he would place the recipe alongside “the Frying of Latke 49” (har har) in his “Gravity’s Rainbow Cookbook.” The band Radiohead, the film The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai (1984), and the novels of William Gibson all pay homage to Lot 49 with references large and small. If there are five hundred Pynchon-inspired tattoos on the world’s bodies (give or take?), I’d wager that at least four hundred of them are of a muted posthorn. And if you’ve read only one Pynchon book, this is almost undoubtedly it. As Gravity’s Rainbow says of a magazine’s secret title, “Those Who Know, know,” and Lot 49, while too academically central now to ever be a cult novel, calls out to its readership to form mysterious Tristero-like communication networks of their own, one insider allusion to Yoyodyne or forged stamps at a time.

Speculating about what we would do without Lot 49 becomes more than an interesting thought experiment when we consider that Pynchon came close to not giving it to us at all. Scholars (at least those who acknowledge the challenge) have had to square the book’s role in defining Pynchon with his apparently low opinion of it, glimpsed in an elliptical remark at the end of the preface to Slow Learner, his 1984 reflection on his early career: Lot 49, he writes, was a “story,” “marketed as a novel,” “in which I seem to have forgotten most of what I thought I’d learned up till then.” Some (such as Terry Reilly) think Pynchon’s confessional voice in Slow Learner is a put-on, one more layer of masking for a paranoid recluse. Boris Kachka, though, in a rich 2013 investigation, describes Pynchon after his first novel as “eager to break with” Lippincott (publishers of V. [1963]) “and rejoin [editor] Cork Smith, since departed to Viking.” Letters by Pynchon from 1962 to 1964, available at the Harry Ransom Center, support claims about his dissatisfaction with Lippincott. Pynchon, Kachka continues, “saw Lot 49” not as his next major work but “as a quickie ‘potboiler’ meant to break his option with the house—forcing them to either reject it, liberating him, or pay him $10,000.”

Lippincott paid, and the so-called quickie potboiler became indispensable to American literature. Some may say, justifiably, that indulging the counterfactual of a Lot 49-less world, or one where we critically consider Pynchon’s dismissal of his work, just expands fallacious thinking about authorial intention—for the world we have does include Lot 49, as well as the prodigious academic infrastructure that has been built around it, along with a lasting collective judgment of its high-cultural value. Trust the tale, and all its resonances, not the teller. But here the image in the mirror that Oedipa has long held up to readers gains further definition: by thinking about how Lot 49 could have been withheld from us altogether in 1966, we become even more like the Oedipa who, tracking clues in The Courier’s Tragedy, traces the definitive text of the play from a director’s edited script to a dissolute scholar and finally to a used book store where she hears she can get a copy—now burned to the ground for insurance money and, anyway, owned by the ex-lover of hers who may be orchestrating this whole charade. Where do we find what Gravity’s Rainbow later calls “the Real Text,” while still acknowledging the interdeterminacy and contingency of its origins?

Luckily, unlike Oedipa, we are obsessed with a sign system that, while it reflects our solipsistic interpretations, we can still hold in common around the seminar table. There’s ultimately nothing to be done except get together and talk some more about the book. Many of the ideas in this essay will be subjects at a roundtable I will chair at MLA 2016 in Austin, “The Crying of Lot 49 at Fifty.” David Cowart, Brian McHale, Angus Fletcher, Ali Chetwynd, Katie Muth, and I will unpack the novel’s history, reception, and critical omnipresence, wondering over how Pynchon’s Boeing work influenced the book, how postmodernism’s relationship to indeterminacy may depend on it, and how Paul Thomas Anderson’s compelling adaptation of Inherent Vice (2014) changes our thoughts about Lot 49’s own cinematic possibilities. We’ll clear our throats and spread our arms in gestures that belong to the priesthood of critical culture, but final revelations will be duly deferred. Hope to see you there. For more info on this gathering, write by WASTE.

Jeffrey Severs is assistant professor of English at the University of British Columbia. He co-edited (with Christopher Leise) Pynchon’s Against the Day: A Corrupted Pilgrim’s Guide (U of Delaware P, 2011), and he has written essays on Vineland (for Pynchon Notes) and Gravity’s Rainbow (forthcoming in Twentieth-Century Literature). His book, David Foster Wallace’s Balancing Books: Fictions of Value, will be published by Columbia University Press in 2016.

Add new comment